CURATORIAL PROGRAMME #10

Róża Litwa / Rafał Bujnowski. PARA / STEAM

22.09-30.11.2023

Join us for the duo exhibition of Róża Litwa and Rafał Bujnowski.

See you at the opening on September 22 (Friday) at 6 PM.

The exhibition presents an artistic dialogue between Róża Litwa and Rafał Bujnowski. These two are not creating joint works, but building a joint exhibition. Its opening was preceded by meetings and discussions. In the gallery, Róża and Rafał talk without words but through pictures. The exhibition was born from the intuition that they had something to say to each other. They speak two different languages, but they understand each other.

When arranging a joint exhibition, Róża and Rafał did not set themselves a problem that they intended to solve by joining forces. The topic is the encounter between an artist and an artist who notice each other, respect each other and are curious about what they will see when they look at their own creation through the prism of the other person’s work.

At this exhibition — before we answer the question: what they both say — we ask another question: how they say it.

If the exhibition were a conversation between two people, we would listen to the tone of their voices. We would read lips. We would look at body language, facial expressions and gestures.

If their works were texts, we would study not only the written words, but also — and even above all — the handwriting, the composition of the ink used for writing, the matter and texture of the surface on which the signs were placed.

Or maybe Róża and Rafał actually, in a sense, write the paintings they show at the joint exhibition?

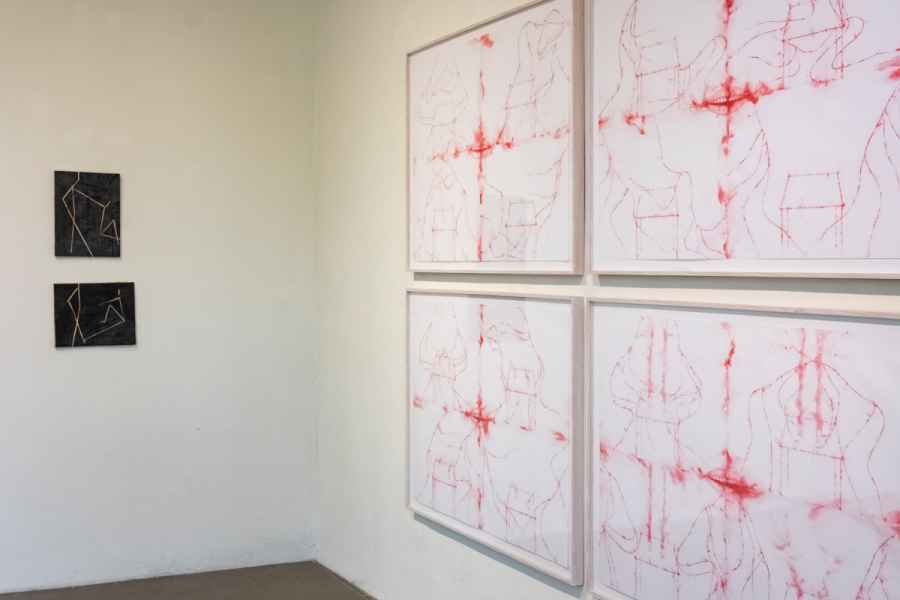

Róża’s works look as if they were written in blood. Rafał invites you to write his fire paintings.

Róża uses lines masterfully. Her painting balances on the border of drawing, while drawing is close to calligraphy. The artist’s favourite canvas is paper; Róża draws signs on it that form the shapes of human figures — or rather, she draws figures that are signs of a kind. She is a figurative artist in a deep and specific sense of this concept. The human figure is the leitmotif of her work, the basic phrase of the artistic language. Róża develops the discourse of her art by repeating, transforming and inflecting this phrase in various ways. She uses it to build complex sentences and whole stories.

Focused on the motif of the human figure, the artist paints people, but does not depict people. The heroes and heroines of her works have no names, pasts or futures. It happens that Róża composes figures of people into structures or patterns in which an anonymous individual has a right to exist only to the extent that he or she is part of a larger whole.

The figures drawn by Róża are conventional, like signs, but at the same time they are specific, almost biological in their presence. It is the dialectic of conventionality and physicality that seems to be the source of tension in Róża’s depictions. The people in her works do not have faces, but they sometimes have mouths, noses, or eyes. They also have spines, nervous and circulatory systems, and organs. The sight of these figures provokes us to recall Agamben’s category of “bare life”; these are people who do not have an “identity card”, but whose bodies are strongly outlined by the artist, teeming with life. Let's look at the works that Róża prepared for the Para / Steam exhibition. They are painted with red paint. The association with blood is almost irresistible, even painful; thin, sharp lines on paper look like scratches on skin. Around the lines, the paint spreads into irregular spots; these are cuts rather than brushstrokes, wounds that “bleed” — and at the same time form the outlines of characters. Róża shows them in pairs and studies their mutual relations. Are these characters dancing — or are they fighting? Do they love each other — or do they hurt each other? Or are dance and fight, love and violence, one and the same here: the naked, exposed bloodstream of life?

The dialectic of what is imagined in the works and their intense physicality marks the point at which the paths of Róża and Rafał intersect at the Para / Steam exhibition.

Rafał Bujnowski has recently been creating paintings in company with fire. It is the fruits of this cooperation that are shown at the exhibition, alongside Róża’s works. The artist uses pyrography — “writing with fire”. Or rather, it evokes it from the periphery of visual culture; it is a technique not taught at academies of fine arts, associated with non-professional work, but even more with inferior artistic crafts and the souvenir industry, whose paradigmatic pyrographic product are alpenstocks decorated with burnt patterns. Many of the effects of pyrography are banal and kitsch; Therefore, it is easy to overlook both the artistic and symbolic potential of “writing with fire”. Rafał wants to liberate them, bring out the noble dimension of technology, in which an element with transformative power, creative and destructive at the same time, plays such an important role. The artist is aware that flames are an accomplice that is both powerful and dangerous. A kind of prologue to the series of pyrography are the works on paper shown at the exhibition, saved from the fire that destroyed the artist’s house a few years ago. All of them were affected by fire to a greater or lesser extent — they are burnt, blackened, charred. And also transformed; these are paintings started by Rafał, but finished by flames.

In the series of pyrography works created in recent months, the order of work is reverse: it usually starts with fire, then the artist starts working. The canvas is wood. Does it matter for the expression of the paintings made on it that they were created in Rafał’s studio on Fuerteventura, an island where no trees grow in its natural ecosystem? And does it matter that Fuerteventura is a volcanic island, literally carved by the element of fire? (1)

Well, the creative process always matters, especially in the art of Rafał Bujnowski, who has always devoted a lot of attention and reflection to it, revealed it and incorporated it into the discourse of his works. Between the lines of subsequent cycles and realisations, Rafał is constantly writing a kind of treatise on painting and its ontology. He puts painting to the test, checking the limits of our faith in a painting. It is a faith that makes us see something more than an object, a canvas, boards, pigments in a painting. While carrying out these tests, the artist invited various forces, such as chance, the laws of physics, and optical illusions, to participate in the process.

The processual element, as well as the performative dimension of creating images — generally important in Rafał’s work — plays an exceptionally important role in pyrography. There is even something ritualistic in the way they are created, in the sense that a ritual is a sequence of actions leading to symbolic results and also involving non-human actors of reality, for example the forces of nature.

To an island where the only trees are those planted and cared for by humans, the artist brings wood from the mainland in a suitcase. Sometimes the wood is boards from a DIY store, sometimes boards intended for writing icons. Still other works were created on pieces of wood from construction sites in Fuerteventura.

Then the artist treats the wood with a burner — or lights a fire in the middle of the day and puts the boards in it in full sunlight. Under the influence of fire, wood changes colour and texture. Painting with fire is balancing on the edge. Beyond the edge is destruction and ash. The game is to stop a moment earlier, at the moment when the fire begins to bring out the image enchanted in the wood, but has not yet consumed it. Working with fire is like carving stone; the shape that the artist forges is, in a sense, always present in the block of material, it just needs to be extracted.

The fire leaves traces on the surface of the wood, as if giving hints. Sometimes it suggests a landscape or sunset, other times it suggests the outline of a figure. The artist follows the traces left by the flames. How far does he follow them? It depends. Sometimes he painstakingly extracts an image scratched by fire, using carpentry tools, removing layers of charred matter, revealing intact wood, or carving drawing lines into a board. At other times it stops almost immediately, subtly emphasising what has appeared on the board after the work done by the fire.

This process is similar to developing a photograph, but in this case the developer is a mixture of flames and the artist's intuition and actions. From here it’s only a step to thinking about summoning spirits; and there is indeed something ghostly in Rafał Bujnowski’s pyrography. However, these are not apparitions coming from the afterlife, but rather a spirit enchanted in matter.

The animistic element is indelible from the ontology of a work of art. We treat images as objects endowed with specific subjectivity, things that work, speak to us, show something. In the works that Róża and Rafał show on Para / Steam, the animistic dimension of the work of art comes to the fore especially clearly. Given the physicality, the particular “anatomy” of these artefacts, it is difficult to think of them as inanimate objects; paper is associated with skin, paint with blood, wood is flesh. If the works of two artists were a text, it would have the character not of a discourse but of a sequence of ideas coming to life in the minds of the recipients. The ideas with which Róża Litwa and Rafał Bujnowski fill their joint exhibition are full of life; and in this case this statement is not a worn-out metaphor; they can be understood literally. It is from life that both the lyricism and the cruelty of the works of both artists, their brutal delicacy, flow. Life is also a medium in which both Róża and Rafał work, and thanks to which, using two different languages, they understand each other so well without words.

__

(1) If the burnt works saved from the fire were treated as a prologue to pyrography, Rafał Bujnowski’s sculpture “Cyparis” (2009) present at the exhibition would be a footnote to them. This is a portrait of a man made by an artist from volcanic sand from the Caribbean. The protagonist of this work, Auguste Cyparis, was one of only a few survivors of the destruction of the port of St. Pierre on the coast of Martinique. In 1902, the city was destroyed by a volcanic eruption. Nearly 30,000 people died. Cyparis survived because at the time of the disaster he was imprisoned in the local detention center, in a windowless solitary cell. The fact Rafał’s sculpture entered the exhibition is also a kind of response to the sculptural realisations of Róża Litwa. The artist creates ceramics, that is, works in which fire plays a role, just like in the pyrography.

Text: Stach Szabłowski